The Sequence 1/9-1/15

Disparities in Genetics Knowledge and Trust in Medical Research, Genetic Analysis of Gregor Mendel, New Risk Factors Associated with Gastric Cancer, Human DNA is Still Evolving

Disparities in genetics knowledge and trust in medical research in a cohort of dilated cardiomyopathy patients

Ni et al. studied the association between genomics knowledge and trust in researchers among dilated cardiomyopathy patients of varying racial and ethnic backgrounds. The study also addressed whether these differences may lead to varying social determinants of health.

Who was analyzed in this diverse population?

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional study involving more than 1,000 idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy patients enrolled in heart failure programs between mid-2016 and early 2020. Among 1121 participants, 41.4% were Black and 8.5% were Hispanic.

What did they find?

The investigators found that genome sequencing knowledge level was lower in Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients versus non-Hispanic white patients, and trust in medical researchers was lowest in non-Hispanic Black patients. Higher trust levels were associated with a greater knowledge of genome sequencing within all different racial and ethnic groups.

What’s the takeaway?

Despite their presence and influence in the U.S., racial minorities continue to face barriers to accessing healthcare genetic services. With the increasing emphasis of genetics in healthcare, it is critical to understand genetics knowledge and beliefs in historically underserved populations.

Practically, these differences should be addressed in genetic services appointments, including genetic counseling, to ensure that true genetic risks to offspring and uncertainty around disease penetrance and expressivity are well understood. Not only does this information have implications for medical management, but the comprehension of this information is critical to understanding and trust between patients and providers.

I think it’s worth mentioning again here the All of US program, a research program dedicated to helping us increase our understanding of each other by building one of the most diverse health databases in history. In fact, now that it’s enrolled more than 560,000 people, the study has begun giving back results.

Genetic analysis of Gregor Mendel

Gregor Mendel, the ‘Father of Genetics’, was the first person to begin to understand inheritance. For context, this is before the term ‘gene’ even existed; his foresight and observations were pretty incredible.

You may recognize Mendel by his work with peas; one of the first experiments we all learn about in ‘intro to genetics’ courses everywhere. By observing the offspring of peas with different characteristics and recording the traits- think height, pod shape , seed shape, pea color, and so on- he gained insights into how the plants passed on these different traits to their offspring.

Born in 1822, last year would have been Gregor Mendel’s 200th birthday. So to celebrate, scientists did what they felt was the best way to pay homage- they analyzed his DNA.

How?

Good question- as Mendel has been buried in the Czech Republic since 1884. To begin, the scientists had to get permission from the monks of Saint Augustine’s Order in Prague, where Mendel lived as a monk, to dig up his body from his grave at Brno’s Central Cemetery in Czechia. Once receiving permission, they extracted the DNA from his remains.

Since Mendel was buried in the same coffin as 4 other Augustinians, the researchers had to verify the DNA they were looking at was actually his. They gathered DNA from some of Mendel’s personal possessions- items now local museums like microscopes, eyeglasses, written records, etc- and they were even lucky enough to find a hair of his stuck in a book. By looking at DNA from all that, and comparing it to DNA in the skeleton, they felt certain that they'd found Mendel's body.

Interesting. What did they find?

Mendel’s DNA revealed genetic variants linked to diabetes, heart problems, kidney disease, and most intriguing- a mutation, or harmful change in the DNA, associated with epilepsy and neurological issues. Although it does make sense, as Mendel was known to have severe nervous breakdowns throughout his life.

What’s the takeaway?

Gregor Mendel, an intellectually curious and persistent man, was studying inheritance at a time when it was commonly accepted that heredity is exclusively passed through the semen of men. He was open-minded and forward thinking; he knew there had to be more to theory of inheritance than what was understood in the early 1800’s, and he was right. I feel, like the research team in Czechia, that Mendel would have been fascinated by what we’ve learned in the last 200 years since his death, and proud to be a part of a new experiment.

HAPPY 200th, GREGOR MENDEL!

New risk factors associated with gastric cancer identified

Liu et al. studied the DNA of 284 Chinese patients with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) in order to identify the rate of mutations in the CDH1 gene associated with it, as well as to identify new susceptibility genes and risk factors that can be used for screening of HDGC.

Tell me more.

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) is an inherited disorder increases the chance of developing diffuse gastric cancer, a form of stomach cancer in which there is no solid tumor, but instead cancerous cells multiply underneath the stomach lining. It’s an adult-onset condition known to be associated with mutations, or harmful changes in the DNA, in the CDH1 gene.

So what did they find?

By analyzing the DNA and tumors of these individuals, the researchers found 1- new harmful genetic variants that they believe is the cause of HDGC in these individuals and 2- a new environmental risk factor that these individuals had in common. Among the 284 patients, CDH1 germline mutations (i.e. they were born with those mutations) were identified in 2.8%, whereas CDH1 somatic mutations (i.e. their tumors acquired those mutations) were identified in 25.3%. In addition to other mutations being identified in some expected genes that have been known to cause susceptibility to HDGC, additional mutations were also identified at a high frequency (>10%) in genes that had not been associated with HDGC before (MUC4, ABCA13, ZNF469, FCGBP, IGFN1, RNF213, and SSPO genes).

Another interesting result: The study identified a correlation between genetic variation in tumors and the exposure to aflatoxin- a fungal toxin that commonly contaminates crops- suggesting potential interaction between genetics and environment in HDGC.

What’s the takeaway?

This cohort study expands what we knew about genetic susceptibility to HDGC, and provides evidence condemning exposure to aflatoxin as increasing susceptibility to HDGC. Discoveries on the causality of certain types of cancers have a powerful impact on our understanding of the pathogenesis of cancer as a whole, and how we may eventually prevent and treat it.

Human DNA is still evolving

In this newsletter, i’m always talking about gene mutations, or harmful changes in the DNA, within genes. Genes are made up of letters, called ‘bases’; those letters are A, T, C and G, and they string together like beads on a string. There are many, many combinations of those letters, or order of beads, in different people. So, new mutations and other genetic variations are arising in people all the time, within the genes that we all have.

What if we had the ability to make new genes?

Vakirlis et al., a group based from the Biomedical Sciences Research Center "Alexander Fleming" in Greece, studied the DNA of different animals throughout our evolution to see if new genes, not just mutations, also arose over time.

Image Credit: NIH

How would that happen?

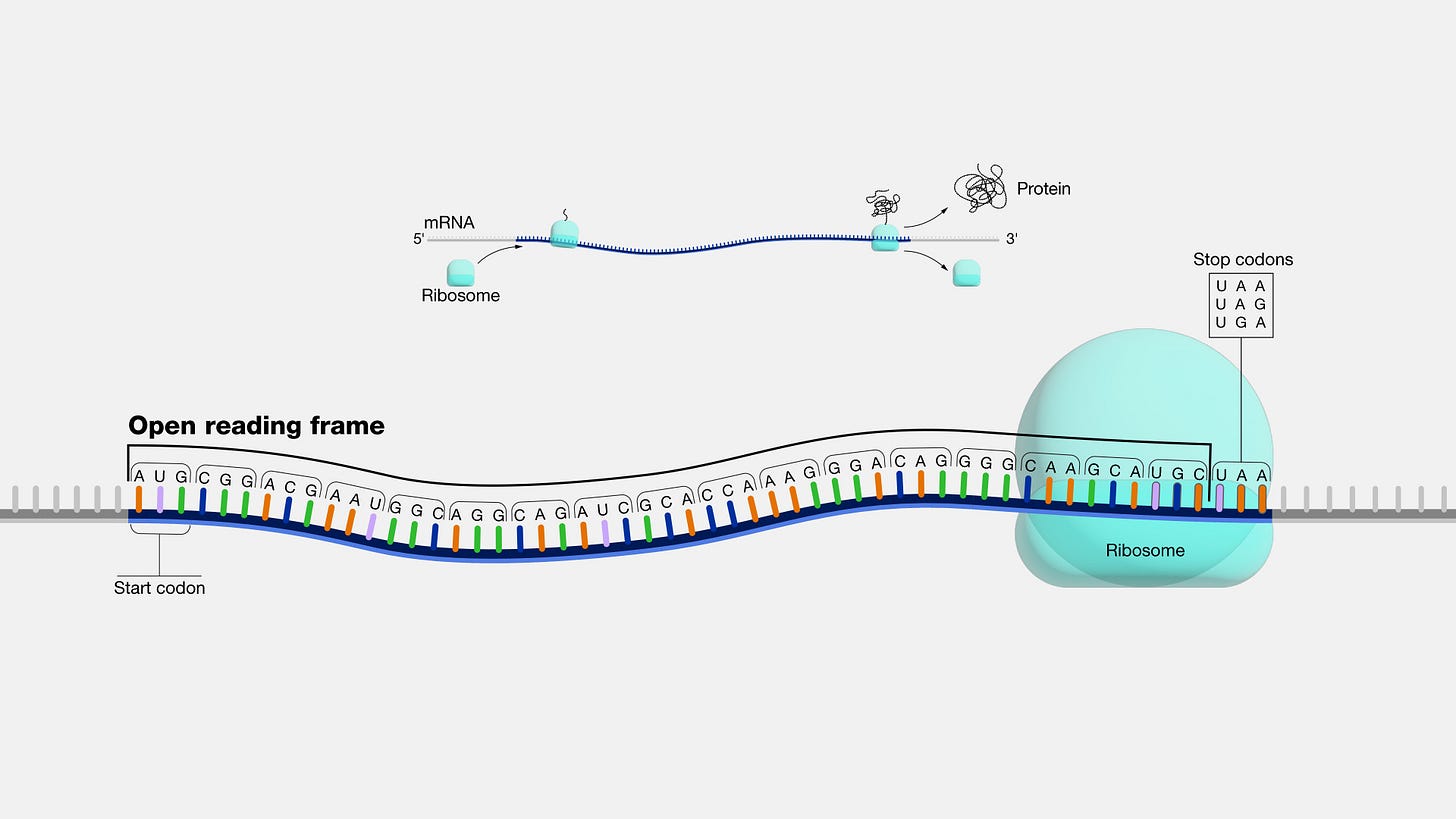

Open reading frames (ORFs). Remember that DNA codes for → RNA which codes for → protein. This happens when a ribosome slides along that string of RNA letters and turns them into amino acids. At some point, the ribosome hits a stopping point (it’s literally called a stop codon), and stops along the string of letters. That whole string of letters before the stopping point? That’s the open reading frame (ORF).

So how could an ORF lead to a new gene? Most ORFs in the body are considered ‘junk DNA’. They’re made up of letters that make protein that is unimportant; not functional. But this team of scientists was wondering if there are some mutations in ORFs that may have created little proteins, ‘microproteins’, that are in fact functional. This would make that ORF a gene.

The results?

The group was in fact able to look at a recently published dataset of human microproteins translated from ORFs, and found cases of small proteins that evolved out of previously nonfunctional ORFs.

What’s the takeaway here?

This is huge! We’re always striving to understand how different medical conditions arise, and these findings mean some may be caused by alterations in ‘microgenes’ or ‘microproteins’ that we didn’t know existed, and certainly didn’t know had any functions in the body.

As humans have evolved, new genes have been born.