The Sequence 2/24-3/2

Mapping the Duration of DNA Replication Errors

Mapping the Duration of DNA Replication Errors

As DNA replicates itself at a rate of 50 nucleotides per second in the body, it is constantly subject to replication errors and damage, leaving cells with thousands of individual DNA lesions at any given moment. The likelihood of developing cancer-related mutations grows as DNA replication errors are passed on during each cell division. That’s why DNA repair systems in the body are so efficient and there are so many genes responsible for protecting against DNA damage. Replication errors in the DNA have a half-life of mere minutes to hours. However, the extent to which DNA damage can persist for longer durations remains unknown.

A new study by Chapman et al. identified DNA lesions that lasted 2.2 years on average, with up to a quarter persisting for at least 3 years. Today, I’ll be discussing the types of variants that result from DNA lesions, what we know currently about the half-life of DNA damage and its relationship to cancer, and the study’s findings on the unexpectedly long life of mutations caused by replication errors.

What is the Relationship Between DNA Errors and Cancer?

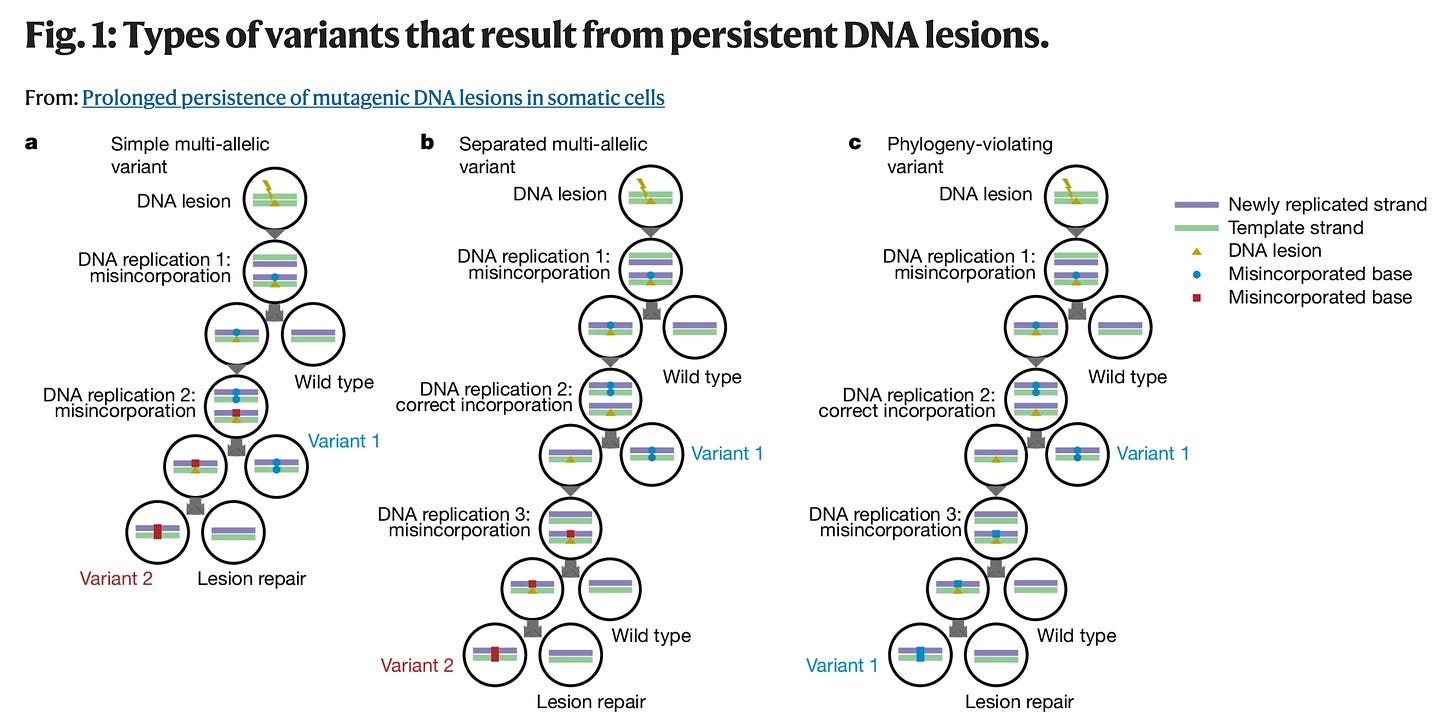

Figure from Chapman et al. 2025

Cancer starts with mutated cells that keep replicating themselves and blending in with healthy tissue. When cells with replication errors grow uncontrollably and spread to other parts of the body, it is cancer. There are various types of mutagenic variations that can occur from DNA lesions, or DNA damage. In the figure published by Chapman et al. above, 1a shows a DNA lesion that persists across two DNA replications. In the first replication, the DNA lesion leads to a mutation in the newly replicated strand. In the second replication, the new mutation is replicated (we now have variant 1), and the original DNA lesion leads to yet a different mutation in the newly replicated strand (variant 2). This shows that the incorporation of several cell divisions after one DNA lesion has the potential to generate a mutation each time the strand with the lesion is replicated; in this example leading to two alternative mutations at the same position in the genome, i.e. ‘multi-allelic’ variants (MAVs). In the same figure, 1c shows that if the DNA lesion leads to the same base misincorporated on the opposite strand during different rounds of replication, the DNA lesion leads to the same mutation and the same variant over and over again, i.e. ‘phylogeny-violating variants’ (PVVs). A given DNA lesion may give rise predominantly to PVVs, MAVs or a mixture of both. A diverse set of mechanisms has evolved to repair DNA lesions such as adducted, methylated or oxidized bases.

What Did Researchers in this Study Do?

In this study, researchers profiled the cell line lineages of somatic cells from 89 individuals. Cells were haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs, n = 39), bronchial epithelial cells (n = 16) and liver parenchyma (n = 48 from 34 individuals). They looked at high-resolution somatic datasets to analyze the cell lineages, or phylogenetic trees, and look for mutations arising from DNA lesions that persisted across multiple cell cycles. They identified PVVs and MAVs by tabulating the number of mutated alleles in each individual and considering factors such as the likelihood that a number of PVVs or MAVs could occur by chance in the same position, and how far apart from one another in the single line of descent the PVVs or MAVs occurred. This information allowed them to understand which variants were generated from the same persistent DNA lesions and for how long.

What Did the Study Find?

In the new study, scientists identified mutations arising from 818 DNA lesions that persisted across multiple cell cycles in normal human stem cells from blood, liver and bronchial epithelium. In haematopoietic stem cells, the majority of persistent DNA lesions generated the characteristic mutational signature SBS19. Overall, 16% of mutations in blood cells are attributable to SBS19, and similar proportions of driver mutations in blood cancers exhibit this signature. The study found the mutation occurred steadily throughout life and even in utero. The authors estimate that on average, a haematopoietic stem cell has approximately eight such lesions at any moment, half of which will generate a mutation with each cell cycle. Mutations endured for 2.2 years on average, with 15–25% of lesions lasting at least 3 years. Of note, persistent DNA lesions occurred at increased rates in donors exposed to tobacco or chemotherapy, suggesting that they can arise from external exposures.

What’s the Takeaway?

Since we know that the chance of creating cancer-causing mutations increases each time these mistakes in DNA are replicated during cell division, it was unexpected to find that DNA lesions can persist for up to three years. It is unknown whether each of these mutations would go on to develop into cancer, and more research is needed to understand the relationship between mutation presence in cell lineage cycles and tumor development. The results from this study indicate DNA lesions that arise from internal and external sources are initially present in low numbers in the genome, but can persist for months to years and can generate a substantial fraction of mutation burden in somatic cells.

https://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/cells-can-replicate-their-dna-precisely-6524830/

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-08423-8

https://www.nature.com/articles/s12276-021-00673-0

https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/her/tree-of-life/a/phylogenetic-trees

https://theweeklysequence.substack.com/p/the-sequence-210-216