The Sequence 8/26-9/1

Advancing Genetic Variant Interpretation for Breast Cancer

Advancing Genetic Variant Interpretation for Breast Cancer

An estimated 310,720 new cases of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed in women in 2024. After covering the utility of polygenic risk scores (PRSs) in predicting breast cancer, and various types of screening for early detection and preventive treatment, I am covering the new set of guidelines for interpreting variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which were approved by the ClinGen consortium last year.

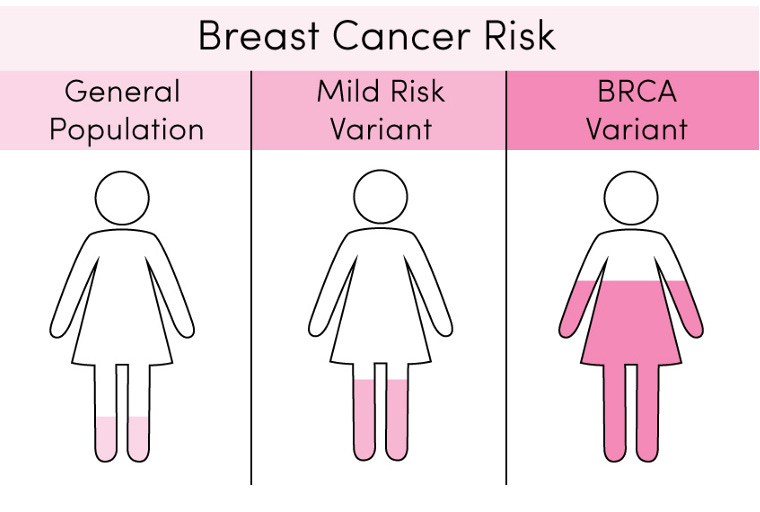

Unfortunately, it’s all too relevant; breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in the United States aside from skin cancer, and 5% to 10% of breast cancer cases are thought to be caused by hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome (HBOC), meaning that they result from pathogenic, or harmful, genetic variants in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. We know so much about the risks associated with variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, in fact, that some feel we’re ready for population genetic testing of these genes, or testing on the entire population, not just people at a higher risk of a genetic disorder. As genetic testing becomes offered more widely, it’s important to understand the criteria involved in classifying genetic variants as benign or pathogenic.

Why does the classification of a genetic variant matter?

The classification of a genetic variant is important because it is the basis for clinical judgment. A positive test that indicates a patient has a pathogenic genetic variant can impact a patient's care, treatment, and genetic assessment. For example, cancer screening has become commonplace for patients with HBOC. We know so much about the risks associated with variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that if a patient has a pathogenic variant in one of those genes, there are strict screening guidelines for them to follow. The American Cancer Society recommends that women at average risk for breast cancer begin screening at age 45. For women with a variant in BRCA1 or BRCA2, however, screening could start as early as age 25. In addition to earlier mammograms, current guidelines suggest that if there is more than a 20% risk of developing breast cancer during the lifetime, one should have a screening breast MRI in addition to a mammogram.

What are the different classifications for genetic variants?

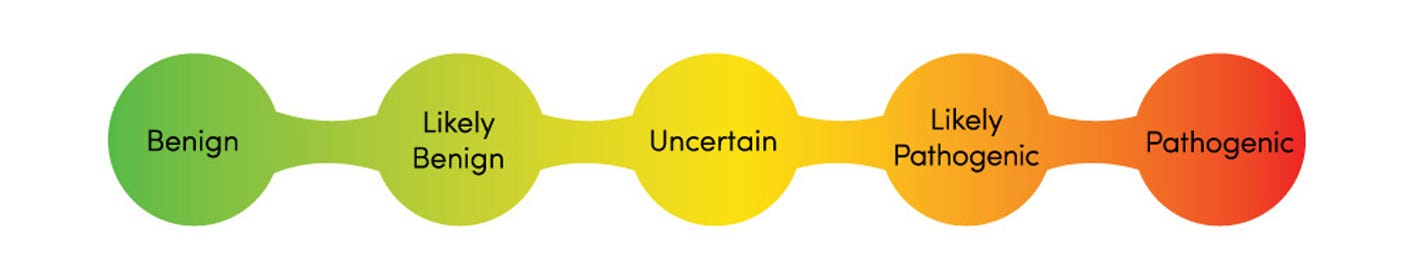

The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) has published guidelines for laboratories to use in their interpretation of genetic variation. The classification of genetic variants based on the ACMG/AMP guidelines is a five-tiered scheme which assigns pathogenicity from benign (not disease causing) to pathogenic (disease causing). The guidelines describe the quantity and quality of evidence needed to classify the variant as:

Pathogenic

Likely pathogenic

Variant of uncertain significance (VUS)

Likely benign, or

Benign

The guidelines assign a strength level to various evidence criteria and require various combinations of strong, moderate, and supporting evidence for a confident classification. Pathogenic variants in disease genes related to phenotype, or symptoms, indicate that a cause of the patient’s symptoms has been identified. Clinically, both pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants are treated the same—as if they are likely disease causing. If the classification of the variant is as a VUS, it means that at the time of interpretation, there is not sufficient evidence to determine if the variant is related to disease or not. According to the ACMG/AMP guidelines, a VUS should not be used in clinical decision-making. Pathogenicity determination should be independent of interpreting the cause of disease in a given patient. For example, a variant should not be reported as pathogenic in one case and not pathogenic in another simply because the variant is not thought to explain disease in a given case.

What are the new guidelines for classifying genetic variants associated with breast cancer?

Until now, variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have been classified using the ACMG/AMP guidelines mentioned above. In this study that outlines the work of an international consortium called ENIGMA, the group converted its own classification tiers to match the ACMG/AMP structure and resolve uncertainty in classification.

Interestingly, after initial review of the ACMG/AMP criteria for relevance to interpretation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants, the ENIGMA investigators determined that 13 of the existing ACMG/AMP criteria were not applicable to the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Additionally, several criteria were added to follow recommendations from parallel work of the ClinGen Splicing Subgroup to encompass RNA splicing experimental data in variant classification. Some specific examples of criteria considered inapplicable to BRCA1 and BRCA2:

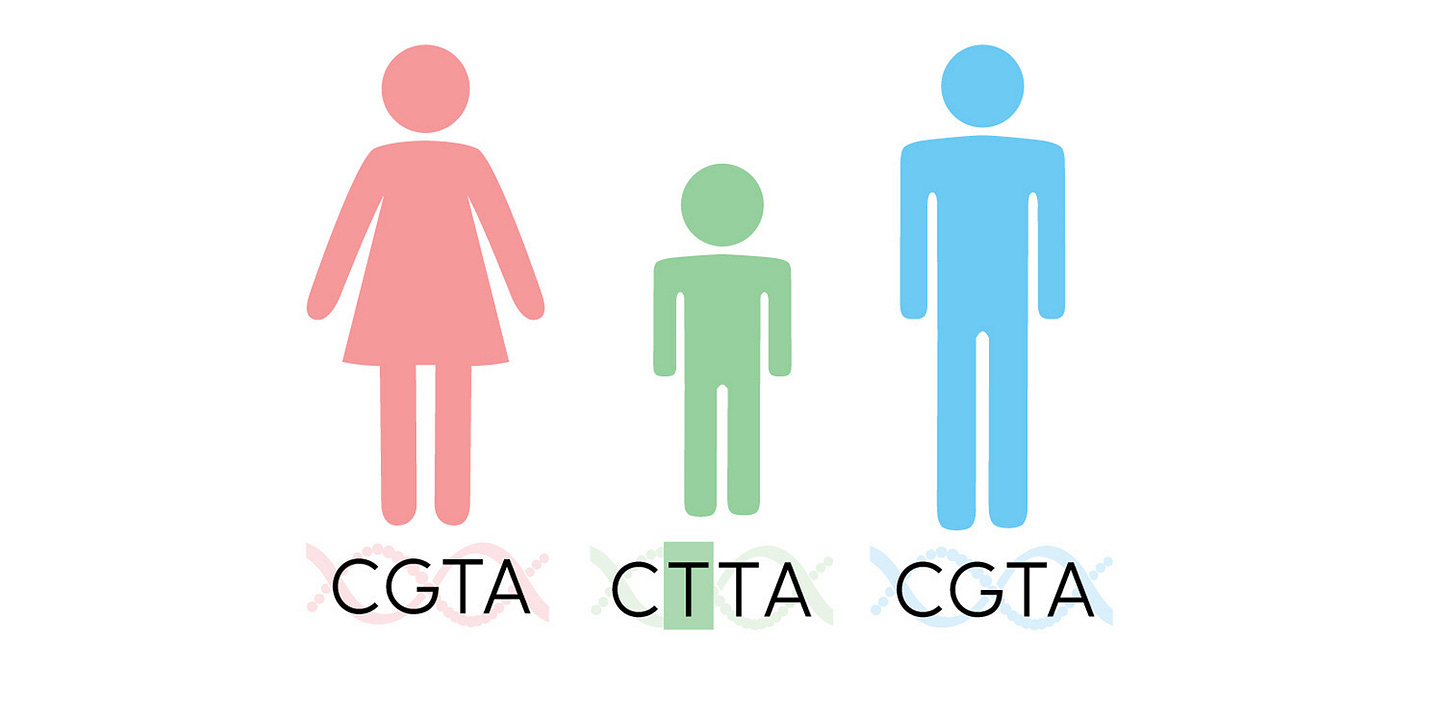

PS2/PM6: These criteria serve as evidence for pathogenicity if a variant is de novo, or a new variant not inherited from parents. These criteria were regarded as inapplicable because of how commonly BRCA1/2-related cancers appear in the general population.

PM1: This criterion serves as evidence for pathogenicity if the variant is located in a hot spot or critical domain of the gene. This criterion was regarded as inapplicable because this kind of evidence is automatically captured as a component of bioinformatic analysis based on missense prediction tools and does not need to be manually assessed in variant classification.

PS4: This criterion serves as evidence for pathogenicity if the variant is more prevalent in affected individuals when compared to controls. This criterion was regarded as inapplicable because there is overlap with criteria regarding variant population frequency, and the evidence between cohorts varies too widely to be accurate for a given variant in BRCA1/2.

Once ENIGMA solidified their new classification methodology, a group of volunteer curators performed a pilot analysis of 40 variants. The preexisting classifications for the pilot variants were as follows: 13 conflicting or uncertain, 11 pathogenic, three likely pathogenic, one likely benign, and 12 benign. Compared to the original assessments, classifications were resolved for 11 of 13 uncertain variants. Analyses using the new guidelines also resolved variants that were previously likely pathogenic or likely benign to be converted to pathogenic or benign.

What’s the takeaway?

The ENIGMA consortium has developed new guidelines for classifying genetic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes associated with breast cancer. These guidelines are based on the ACMG/AMP evidence criteria, but they include several modifications to better capture the specific nuances of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants. Although the new criteria pilot analysis of 40 variants proved successful and resolved the classification for 11 of 13 uncertain variants, the new guidelines must get an official stamp from the FDA through the ClinGen system. In the meantime, the team plans to make their new guidelines publicly available in the BRCA Exchange portal.

Newsletter Sources:

Images: https://www.genome.gov/sites/default/files/media/files/2020-04/Guide_to_Interpreting_Genomic_Reports_Toolkit.pdf

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html

https://theweeklysequence.substack.com/p/the-sequence-1121-1127

https://theweeklysequence.substack.com/p/the-sequence-109-1015

https://theweeklysequence.substack.com/p/the-sequence-129-24

https://www.genomeweb.com/cancer/improvements-breast-cancer-variant-interpretation-emerge-international-effort?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=GWDN%20Thurs%20PM%202024-08-15&utm_term=GW%20Daily%20News%20Bulletin

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html

https://www.yalemedicine.org/conditions/hereditary-breast-and-ovarian-cancer-syndrome-hboc

https://theweeklysequence.substack.com/p/the-sequence-325-331

https://theweeklysequence.substack.com/p/the-sequence-821-827

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/american-cancer-society-recommendations-for-the-early-detection-of-breast-cancer.html

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/breast-cancer/hereditary-breast-cancer#:~:text=%E2%80%9CFor%20women%20with%20a%20family,screening%20when%20you%20are%2030.

https://blueprintgenetics.com/variant-classification/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1247/

https://www.genome.gov/sites/default/files/media/files/2020-04/Guide_to_Interpreting_Genomic_Reports_Toolkit.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1098360021013708

https://www.acmg.net/

https://www.amp.org/?/MolecularPathology&gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAjwodC2BhAHEiwAE67hJJDc548cCUAkTGPoRwVxe1Zwq21-_3ZexdwPFEAJi7TTD-OZYb_RMBoCNyEQAvD_BwE

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25741868/

https://blueprintgenetics.com/resources/vus-the-most-maligned-result-in-genetic-testing/

https://www.cell.com/ajhg/abstract/S0002-9297(24)00257-X?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS000292972400257X%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

https://enigmaconsortium.org/

https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/genetics-dictionary/def/de-novo-mutation

https://www.genome.gov/news/news-release/ClinGen-setting-standards-for-when-genes-and-their-variants-matter-in-disease