The Sequence 12/26-1/1

Genetics of Dog Behaviors, New Gene Associated with Childhood Glaucoma Identified, A Way to Detect Liver Cancer Before it Develops, Outcomes of Babies Born to Zika Virus-infected Mothers

Happy New Year, Sequence subscribers! I am so grateful for the time you take to skim through the Weekly Sequence, and I wish you and your loved ones a happy, healthy 2023! Looking forward to sharing more exciting discoveries in the new year!

So to start 2023 off with a fun one… dogs :)

New discoveries on the genetics of dog behaviors

For years, dogs have been genetically modified, i.e. bred, to do things such as herd or protect livestock, kill vermin, and hunt. This week, a team at the National Human Genome Research Institute identified specific genetic changes contributing to different behaviors amongst dog breeds.

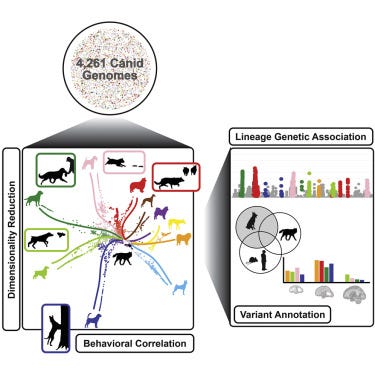

Above: Graphical abstract by Dutrow et al. 2022

Cool. How did they do that?

The team studied DNA samples from more than 4,000 dogs, along with survey data answering questions about behavior in more than 46,000 dogs. The DNA was analyzed with the use of GWAS; explained in this past Sequence newsletter.

Analyzing the DNA samples allowed the researchers to identify the genetic relationships between them until they were able to separate them into 10 major lineages, or lines of ancestry. After looking at the survey data, those 10 lineages largely correlated with the tasks for which the dogs were originally bred. This indicates that similar genes correlate with, and are likely responsible for, behaviors across dogs bred for the same tasks.

What did they find?

Let’s break this down. To begin, the researchers 16,250 variants, or changes in DNA, associated with specific dog lineages. Of those genetic variants unique to different dog lineages, only 76 variants were found that 1- code for protein (i.e. have a job in the body), and 2- are predicted to have a moderate-to-high impact on development.

The team was able to see some serious patterns when it came to sheepdogs. Why? Well, as herding dogs, they have complex abilities when it comes to motor movements in order to shuffle livestock around in intricate ways. Within sheep dogs, they discovered an increase in genes involved with, or near other genes associated with, axon guidance and ephrin signaling. Both of these tasks are involved in brain development and behavior. In fact, one of those genes, called EPHA5, has been tied to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in humans and anxious behaviors in other mammals. This could help explain both the hyper-focus sheep dogs have when given a task, as well as their high energy.

What’s the takeaway?

Ultimately, this study identified genes associated with behaviors in dogs that we also know are associated with human neurodiversity. This could mean that there is a crossover between genes involved in behavioral patterns of both dogs and humans. So, more we learn about Sparky, the more we learn about the evolution of humankind.

New gene associated with childhood glaucoma identified

Fu et al. studied the DNA of three families with autosomal dominant patterns of childhood glaucoma in order to identify whether there are certain changes in the DNA that are linked with it.

Tell me more.

Glaucoma is a progressive blinding disease that causes loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and irreversible degeneration of the optic nerve. It’s common to see glaucoma run in families. Although it can affect people across their lifespan, we’re talking about childhood-onset here, which is much more rare; so rare that we only actually know 10 of the genes that cause it.

So what did they find?

By analyzing the DNA of these three families and seeing which family members with and without childhood glaucoma share and don’t share genetic variants, the team identified a new mutation, or harmful genetic variant, they believe is the cause of the condition in these families. That variant is the p.Arg1034 mutation in the THBS1 gene. Not only did the genetic mutation segregate (match) among family members with childhood glaucoma, mice studies showed that mice with this genetic mutation had elevated intraocular pressure, reduced ocular fluid outflow, and RGC loss (all things you see in glaucoma). Furthermore, cell studies showed protein misfolding: a sure-fire sign of a genetic mutation with a significant impact.

What’s the takeaway?

There are surely genetic causes of many conditions out there that have not been discovered. With further studies, significant genetic mutations identified in research like this can be used to help people estimate their risks to pass on conditions like childhood-onset glaucoma. This can lead to either genetic testing prenatally, or earlier detection postnatally. The families studied here now have a clear understanding of the cause and effect of the childhood-onset condition running in their families.

A way to detect liver cancer before it develops

Researchers used cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis to identify biomarkers in the blood that predicted the development of liver cancer.

What is cell-free DNA?

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is essentially DNA that is released from cells into the circulatory system throughout the body. You may be familiar with cfDNA testing as it relates to noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), a now pretty standard test pregnant women receive to detect potential genetic conditions in their babies. This works because some of baby’s DNA is also floating around in pregnant mom’s blood.

Got it. What did they find?

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University developed special sequencing, a “fragmentome” analysis, which looked at- you guessed it- fragments of DNA. Specifically, the test identified genome, chromatin (i.e. carriers for DNA), and transcription factor binding (i.e. protein making) site shifts that were present in samples from 75 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), aka liver cancer, patients that were not in samples from 133 other participants. Those other participants may have been high risk due to having other liver conditions, but none of them have HCC.

They were able to calculate the impact of these fragmentome variations using an artificial intelligence approach known as DELFI (DNA evaluation of fragments for early interception), which they had come up with prior to this specific research.

The takeaway?

Researching biomarkers in cfDNA seems to be a booming area of research. See my first post about it only a month ago here. Discoveries like this one make a big difference because cfDNA can be analyzed with only a blood sample. It’s accessible, noninvasive, and can potentially detect cancer earlier than invasive technologies. This is a win for everyone.

Bonus Article: In other cell-free DNA news, we may not even need dad for carrier screening during prenatal genetic counseling anymore.

A nucleotide-sized update:

Study reveals outcomes of babies born to Zika Virus-infected mothers

Remember Zika Virus? Yup. That one. When Zika Virus was at its peak, pregnant women weren’t supposed to travel, well, period, but especially to warmer countries where they are at higher risk of being bitten by a mosquito infected with the virus.

Finally, a study came out with insight on the more long-term effects of Zika Virus on babies born to Zika Virus-infected mothers. The study was able to gather a large number of participants since the peak of the virus was a while ago now.

What did we already know?

We have known for a while that babies who are exposed to Zika during pregnancy have an increased chance of certain birth defects and developmental problems known as “congenital Zika syndrome” (CZS). Babies who have CZS can have a very small head and brain, severe brain defects, eye defects, hearing loss, seizures, and/or problems with joint and limb movement. We have also known that there is a risk for miscarriage and stillbirth.

What’s the new information?

The new information clarifies some of these risks and provides more clear data on how often these effects happen. Using data for 1,548 women, the team saw miscarriages in 0.9 percent of pregnancies, and stillbirth in another 0.3 percent. For infants born live, the researchers identified microcephaly in 4 percent. Other children had neurological, auditory, ophthalmic, and other abnormalities, they report, though usually isolated cases; only 1 percent had multiple abnormalities.

Overall, the findings suggest that approximately one-third of the children born to ZIKA-positive pregnant women present with at least one abnormality compatible with congenital infection.

Please note that these findings are almost word-for-word this little article from GenomeWeb, but they said it so succinctly I couldn’t say it better myself.