The Sequence 12/5-12/11

Epilepsy Treatment by way of ‘Silencing’ Neurons, Treatment of Rare Genetic Condition in Fetus, Utility of Polygenic Risk Scores in Glaucoma, Genetic Variant that is Protective Against Diabetes

Epilepsy treatment by way of ‘silencing’ neurons in epilepsy

Epilepsy occurs when certain neurons, or cells in the brain, are over-excited. Yichen Qiu and her team have been studying a way to ‘silence’ overexcited neurons using gene therapy as a way to treat epilepsy.

Cool. What did they find?

Qiu et al. developed a gene therapy strategy that decreases neuronal excitability in hyperactive neurons and then stops doing what it is doing once the neurons have returned to normal. This is an important distinction from other gene therapy models in epilepsy that have been studied that have, yes, reduced the excitability of neurons, but not been able to reverse the job.

And so how is this different? Let’s start by understanding how the brain fires signals. The brain fires signals according to the balance of ions; think potassium, sodium, etc. Those ions move through the brain via ion channels; there are potassium channels, sodium channels, etc. So, the gene therapy targets genes associated with potassium channels of hyperactive neurons. It alters the way the protein channels are allowing ions through, altering the ‘excitability’, and then alters the channel back once the neurons are firing normally. When studied in a mouse model, the treatment suppressed seizures without other side effects.

Awesome. What’s the takeaway?

Although many medications for epilepsy work by decreasing the excitability of neurons, they work in a pretty non-specific way, meaning they don’t work for many people. This approach may not only mean treatment that works for more individuals with epilepsy, but treatment for other genetic conditions caused by over-excited neurons in the brain.

Treatment of rare genetic condition in a fetus

Tippi Mackenzie’s team at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) treated the first fetus with a form of enzyme replacement therapy in order to prevent the onset of a fatal genetic condition called Pompe disease.

Tell me more.

Infantile-onset Pompe disease begins within a few months of birth. Infants with this disorder typically experience muscle weakness, poor muscle tone, an enlarged liver, heart defects, and have breathing problems. If untreated, it leads to death in the first year of life.

Pompe disease is caused from having two genetic mutations, or harmful changes in the DNA; one in each copy of the GAA gene. When the GAA gene is not working properly, the body cannot make an enzyme that breaks down glycogen. Therefore, in Pompe disease, glycogen builds up in muscle and cardiac cells, causing an enlarged heart and muscle weakness.

In this particular case, the study participant, now a healthy 16-month-old, had had two siblings who passed from the disease before she was born.

Wow. So how was she treated?

The team at UCSF treated the fetus with enzyme replacement therapy, which is the standard therapy for metabolic conditions such as Pompe disease. Remember how we said in Pompe disease, an enzyme that breaks down glycogen isn’t working? Enzyme replacement therapy, you guessed it, replaces it.

Enzyme replacement therapy has been around for some years now, and historically is given to patients every week or two starting at birth (until forever). The problem with that is that in Pompe disease, heart damage begins in utero, before enzyme replacement can begin. So now, with the use of enzyme replacement therapy in the fetus, the baby has a much greater chance of surviving.

How is the patient doing?

Great! When the now 16-month-old was born, she showed no signs of the heart problems seen in infantile-onset Pompe. She has been developing normally, and continues to receive enzyme therapy.

Amazing. What’s the takeaway?

As part of the same clinical trial, the team will use this strategy on eight other conditions. The hope is that the in utero treatment will become standard treatment to prevent complications, especially neurological damage, from Pompe disease and other conditions in utero.

The utility of polygenic risk scores in predicting glaucoma

Researchers from Flinders University in Australia examined data on more than 1,000 patients from the ‘Progression Risk of Glaucoma: Relevant SNPs With Significant Association’ (PROGRESSA) study, a study of individuals with early primary open-angle glaucoma, to evaluate the accuracy of polygenic risk scores in predicting the onset of glaucoma.

What is a polygenic risk score?

A polygenic risk score (PRS) is a number, or a ‘score’ that estimates an individual’s risk for a certain condition. They are used in conditions that are caused by changes in many genes, often coupled with environmental factors.

How are they determined?

Let’s use glaucoma as an example, because that is the health outcome studied in this article. Scientists created PRSs for glaucoma by comparing the DNA of patients with and without glaucoma to determine a ‘collection of genes’ that have more rare variation in the individuals with glaucoma that are not there in the individuals without glaucoma. Then, they can say if you have these ‘X’ number of genes, your PRS for glaucoma is increased.

What did they find?

The group did in fact find that genetically predicted risk for glaucoma using PRS was associated with glaucoma. They know this because over time, patients with higher PRSs were at a higher risk of visual field progression after five years, as compared to the rest of the population.

What's the takeaway?

It would be pretty amazing to be able to use a PRS (which is calculated from only a blood sample, by the way) to identify risks for glaucoma. Understanding our risks for common conditions such as glaucoma can guide healthcare management.

Genetic variant identified that is protective against diabetes

Nag et al. analyzed ~412,000 individuals from the UK Biobank in order to understand genes associated with diabetes.

How did they do that?

Collapsing analysis.

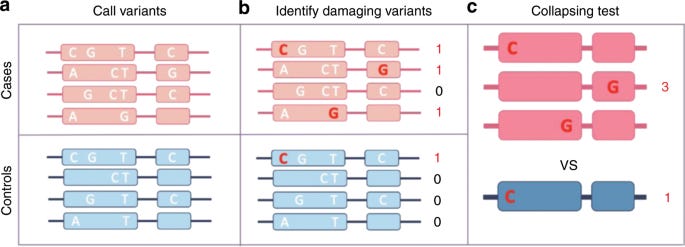

Gene-based collapsing analysis, figure credit: Cirulli et al. 2020

What?

I’ve explained GWAS a few times in this newsletter. You can think of collapsing analysis as ‘GWAS for rare variation’. While GWAS is combing through common genetic variants looking for gene-disease associations, collapsing analysis is looking for rare variation associated with disease.

Collapsing analysis looks at the genomes of a (very) large group of people; this type of test actually requires more samples than GWAS. To analyze the data, researchers use a statistical test called a burden tests to ‘collapse information’ (there is is) for multiple genetic variants into a single genetic score, and tests for association between the score and a trait. An example for this study would be, “look, there’s a rare variant in individuals with diabetes that’s not in the individuals without diabetes”.

What did they find?

Interestingly, the team identified genetic variants associated with not having diabetes. I.e., they’re thinking individuals that have two genetic variants in the MAP3K15 gene are protected against developing diabetes.

Interesting! What’s the takeaway?

By understanding genetic variants that protect from the development of diabetes, those variants may then be able to be a therapeutic target for managing diabetes.