The Sequence 3/6-3/12

23andMe Studies the Microbiome and Parkinson’s Disease, Urologist Encourages Genetic Testing for Prostate Cancer, Exome Sequencing for People with Cerebral Palsy, Long-reads and Population Sequencing

23andMe studies how the microbiome might play a role in Parkinson’s disease

23andMe has teamed up with The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research to study the relationships between both the oral and gut microbiomes and Parkinson’s disease (PD). Parkinson’s disease is a movement disorder characterized by stiffness and trembling of the arms and legs that eventually affect’s one’s ability to walk, talk, and do simple tasks. Many people diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease also suffer from intestinal problems such as constipation.

Interestingly, some researchers have thought for quite a while now that PD might start in the gut. Think of it this way: the disease is caused by buildup of a misfolded protein called alpha-synuclein in the brain; what if that misfolding started in the gastrointestinal tissue, and traveled through the nervous system up to the brain?

This is the aim of this study.

Interesting. And you said 23andMe is doing this?

Yes! This is the part where I want to take a moment to recognize how much 23andMe contributes to scientific research. How? Why? Because they have so many people to study. One of the biggest limitations of most research is the limited number of people there are to study, either because there are only a small number of people affected by a particular condition, or because they’re hard to find and enroll into research. But with the huge number of people participating in 23andMe testing every year, their platform is built for being able to gather big data.

Per the 23andMe Therapeutics website (yes they have a website just about research therapies), over 80% of 23andMe participants opt-in to participating in research. In fact, they have published over 200 papers contributing to research, and are currently looking to enroll patients for a potential new cancer treatment. They also recently released an article explaining that the largest and most diverse genetic study of sickle cell trait ever done showed that being a carrier for sickle cell anemia, or having one copy of the known pathogenic variant in the HBB gene, is associated with an increased risk for blood clots in the lungs.

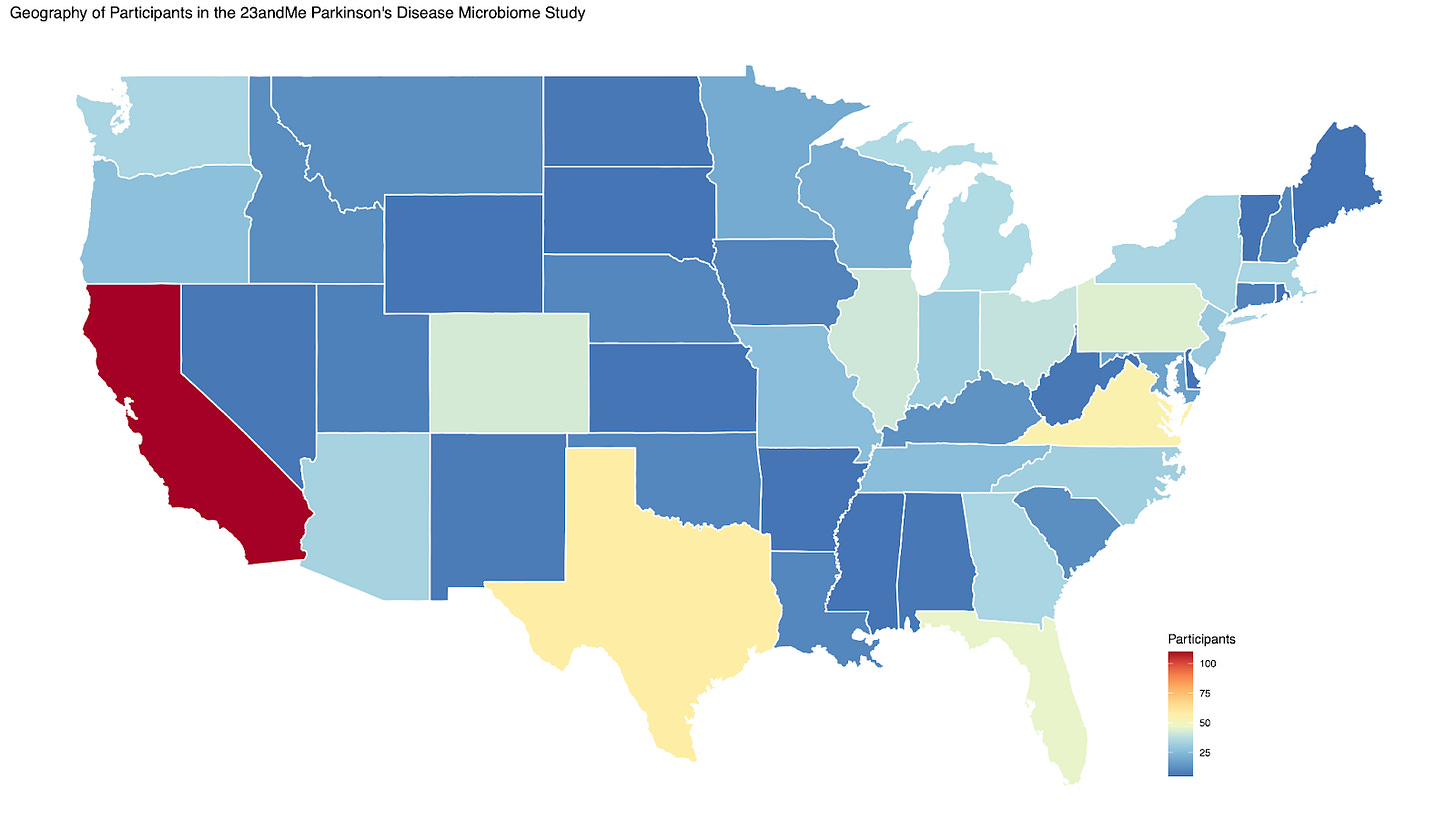

Geography of participants in the 23andMe Parkinson’s Disease Microbiome Study; Image credit: 23AndMe

How exactly are they using their data to study the microbiome and Parkinson’s?

Good question. 23AndMe invited over 650 23andMe customers, about two thirds of whom had reported being diagnosed with PD, to participate by providing stool and saliva samples. 23AndMe then sequenced the samples to identify not only which microbes are present in the samples, but which genes those microbes have. Additionally, the participants completed a detailed survey of microbiome-related questions, such as their age, dietary habits, biological sex, and of course symptoms.

What’s the takeaway?

The primary goal is to identify signatures of PD in the microbiome. Think: are there microbes present in people with PD and not those without? How does that compare to the ages and symptoms of those with PD versus those without? This all will give us an idea of which microbes and/or microbial genes are associated with PD, and maybe even which ones are associated with specific symptoms.

Interested in reading more on the microbiome? This article describes how the gut microbiome may be related to motivation for exercise.

Urologists encouraged to perform genetic testing on patients with prostate cancer

Based on the results Dr. Neal D. Shore acquired from his study performing genetic testing on 182 patients with prostate cancer, Dr. Shore has now taken the stage to encourage urologists to perform genetic testing on patients with prostate cancer.

Tell me more.

Dr. Shore embarked on a mission to evaluate the feasibility of integrating a hereditary cancer risk assessment (HCRA) protocol in urology practice for patients with prostate cancer, and determine the responses of providers and patients to the HCRA protocol. In the end, his study showed that of the 182 patients tested for genetic mutations, or harmful changes in the DNA, 10.4% (N = 19) tested positive for a pathogenic variant associated with prostate cancer. The genes with causative mutations identified in patients included MUTYH, BRCA2, ATM, BRCA1, BRIP1, CHEK2, HOXB13, RAD51C, and RAD51D. Importantly, not all men who tested positive had a family history of cancer.

After the study was completed, 68.3% of providers involved in the study planned to continue to use the HCRA process. Of the patients who answered a survey about their experience, 87.3% had either shared or planned to share their results with family members post-testing.

What’s the takeaway?

Based on this study, incorporation of an HCRA process in a community urology practice appears effective at increasing appropriate uptake of genetic testing in men with prostate cancer. Dr. Shore encourages colleagues to incorporate this process into their practices in order to be able to inform families about increased risk for prostate cancer and to provide better care for patients. Genetic testing is bound to be incorporated more regularly into clinical practice; the question is not if but when.

Full article; Dr. Neal D. Shore on genetic testing in patients with prostate cancer

Whole exome sequencing of patients with cerebral palsy should be considered first-tier testing

Gonzalez-Mantilla et al. reviewed the current literature surrounding the genetics of cerebral palsy and found that cerebral palsy diagnoses could be improved with routine exome sequencing.

So, what does cerebral palsy have to do with genetics anyway?

While a large portion of cerebral palsy is caused by birth complications, think lack of oxygen or extreme prematurity, recent studies have also found that rare genetic variants contribute to cerebral palsy in some cases. But the question has remained, is there real utility in genetic testing of patients with cerebral palsy?

Gonzalez-Mantilla et al. reviewed almost 150 papers published between 2013 and 2022 on this exact subject, eventually landing on 13 articles meeting their inclusion criteria. Based on data for 2,612 individuals with cerebral palsy who were tested by exome or genome sequencing in these 13 papers, the overall diagnostic yield was just over 31%. This is right on par with the diagnostic yield that has been reported for other neurodevelopmental conditions; conditions where exome sequencing is already recommended.

How does genetic testing of cerebral palsy make a difference in patient outcomes?

Right now, healthcare providers will often wait to offer genetic testing to patients with cerebral palsy until there is a ‘reason’ such as the evolvement of developmental delays or autism. A problem, because cerebral palsy is usually diagnosed earlier in age than these other developmental diagnoses, and the longer the wait is for these other symptoms to form, the longer the patient is going without a diagnosis. In short, earlier testing can improve clinical outcomes.

The takeaway?

Genetic testing and mutation analysis should be considered in all patients with Cerebral palsy.

I expect we will continue to identify genes related to cerebral palsy, allowing us to understand more about its mechanism, and making the testing even more useful.

Full Article; read a response to the article here

Should long-reads be used in population sequencing?

Long-read sequencing is DNA sequencing that literally reads longer sequences of DNA at a time than traditional DNA sequencing. There is some debate over whether long-read sequencing should be the testing method of choice in population sequencing (like the All of Us research program, for example).

Cool. Why would we do that?

The thing is, long-read sequencing can pick up some things regular ‘short-read’ sequences can’t. Think: mutations that are made up of ‘repeats’, large and complex rearrangements, large insertions or deletions of DNA, or are located in the intron (the non-protein-coding-portion) of the DNA. It also has better genome assembly (i.e. more accurate sequencing).

That sounds great! Why aren’t we doing it yet?

Historically, long-read sequencing has been considered very costly and full of errors. But it seems like that’s changing. In this week’s article describing the results of the utility of long-read sequencing in large populations, it seems the accuracy has improved. In one study, long reads showed good coverage of a set of 4,641 medically relevant genes, as well the genes on ACMG’s incidental finding list. Additionally, the costs of long-read sequencing have dropped to $1,000 or less per genome.

Essentially, we’re not quite there yet. In the meantime, large-scale long-read sequencing projects will continue to generate data so that we can make more informed decisions on this in the future.