The Sequence 5/1-5/7

Are we Ready for Elective Genetic Testing, Reducing Toxic Protein Levels as a Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease, Gene Therapy as a Treatment for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, A New Way to use CRISPR

Are we ready for elective genetic testing?

Elective genetic testing is genetic testing that people can order at home. Think: 23andMe, Ancestry, Color Genomics and Genopalate. By ordering from these companies, consumers can learn about different health risks, ancestry, and even receive personalized nutrition plans. Here, I summarize an article by 23andMe’s Noura Abul-Husn on the opportunities, as well as the challenges, created by elective genetic testing.

Tell me more.

The opportunities that come along with elective, accessible genetic testing are numerous. This type of testing can detect people at risk for common disorders with known genetic risk factors, such as various cancers and heart diseases. Not only can this empower them to be proactive about their health, it can provide their healthcare providers with additional personal information they may not have known about otherwise.

The challenge? The training most healthcare providers receive has not caught up to the increased accessibility of the genetic testing. This leaves room for errors in interpretation of genetic testing results, or just plain inappropriate follow up.

Luckily, there are professionals that have been trained exactly for this reason, such as genetic counselors (like me) and geneticists. The thing is, our workforce is small, especially when considering that two in 10 Americans have already had a genetic test.

Wow! What should we do?

Make sure our healthcare providers are properly trained in genetics! In this article by Noura Abul-Husn, she outlines some great resources including this practice guideline for genetic counselors and other providers, and this healthcare provider resources page by the NIH. We need enough genetic counselors and providers who are confident in their knowledge of genomics to be available to meet with patients to interpret and explain the results of elective genetic testing. With some patience, fortitude, and a focus on education, I believe we can be there to support the population of people interested in taking control of their health.

Reducing toxic protein levels as a therapy for Parkinson’s disease

Santra Nim and colleagues studied the relationships between different protein inhibitors and Parkinson’s Disease (PD) in order to target particular proteins as a therapy for PD. Parkinson’s disease is a movement disorder characterized by stiffness and trembling of the arms and legs that eventually affect’s one’s ability to walk, talk, and do simple tasks. The accumulation of a protein called alpha-synuclein protein (a-syn) in patients with PD causes neurodegeneration. So, what about inhibiting that protein accumulation to prevent disease?

This is the aim of this study.

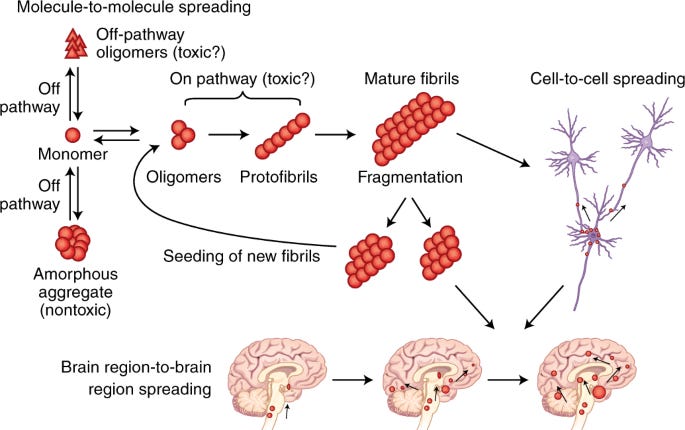

The accumulation of protein in the brain in neurodegenerative disorders. Image credit: Soto et al.

Interesting. How?

To begin, the team worked to identify a protein inhibitor to, well, inhibit the reaction that causes a-syn-mediated neurodegeneration. This meant discovering a protein that disrupts the interaction between a-syn and another protein called CHarged Multivesicular body Protein 2B (CHMP2B). They showed that the peptide inhibitor restored a system that controls intracellular trafficking (think; a traffic guard that helps with things like cell repair and division) and therefore reduced a-syn levels, stopping the process of degeneration.

What’s the takeaway?

With the a-syn and CHMP2B reaction inhibited, there was no longer a build-up of a-syn, and therefore a decrease in degeneration. Not only did this inhibiting reaction stop a-syn build-up, it actually did the opposite and decreased α-syn levels in multiple models.

Now that therapy has been shown to reduce the accumulation of a-syn in human cells harboring disease-causing α-syn mutations as well as in animal models, the α-synuclein-CHMP2B interaction is a potential therapeutic target for neurodegenerative disorders. This is important in more ways than one: not only could this mean a treatment for patients who already have symptoms of PD, it could mean the same process of research to discover treatments for other disorders caused by accumulation of protein in the brain (think: Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington's disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, and Gaucher's disease).

Credit for this one also goes to a fellow Substack writer for this post. Visit EvoluSean’s Toolbox here:

Interested in other PD research initiatives? See this post on 23andMe’s research on PD and the microbiome.

Image credit: Pharmaceutical Technology

Gene therapy as a treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a disease in which the decline in function of the skeletal and heart muscles, and usually total disability and use of a wheelchair, is expected by age 12. This is caused by the absence of a protein called dystrophin, which is critical for the function of muscles in the body. There is currently no treatment for DMD, and care involves management of symptoms by steroids, physical therapy, and medications to prevent heart problems like cardiomyopathy.

What is the new treatment?

Gene therapy! This week, US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Advisory Committee meeting to consider the approval of Sarepta Therapeutics’ gene transfer therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).

The treatment, which first saw positive results in a 2018 preliminary trial, delivers a ‘minature’ version of the gene that is missing in individuals with DMD. The mini-gene enters the body encased in an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector (see my article just below on new CRISPR technologies for more explanation on this). The reason this treatment uses a ‘mini’ version of the gene is because the dystrophin gene is too large to safely insert a whole new one.

In the 2018 preliminary trial, participants showed not only an increase in dystrophin protein, but also a decrease in levels of serum creatine kinase (CK), an enzyme biomarker strongly associated with muscle damage caused by DMD. Since 2018, the drug has shown positive results in two additional clinical trials, putting it on a fast-track toward FDA approval.

What’s the takeaway?

This new gene therapy by Sarepta delivers a partially functional dystrophin gene (remember it’s a ‘mini’ version) that does not cause Duchenne muscular dystrophy to completely go away, but decreases the severity of the disease. This would be life-changing for the 1 in 3,600 individuals living with DMD.

Interested in reading more on the research of treatment for DMD? Here’s a great summary of ongoing research as described by the Muscular Dystrophy Association.

Note, the news about the potential approval for this treatment comes not long after a DMD clinical trial participant was thought to have died from the treatment in question. It was recently reported that the gene therapy he received may not have been his cause of death.

A new way to use CRISPR

Let’s start with the basics: one of the ways to accomplish gene editing is to wrap the gene-editing tools (i.e. CRISPR) in a virus. Almost like a costume or a cover-up to get invited into the cell. Once the virus is in, the gene editing tools can do their thing. This is what we call a viral vector.

Two recently published articles both found alternate ways to encourage the gene-editing tools (CRISPR) to enter the cell.

Tell me more.

To begin, this new method is ex vivo, meaning the new gene sequence is being injected outside the body (think: cells are taken from the body, modified in a lab using gene-editing tools, and then put back into the body); as opposed to in vivo (think: the gene-editing tools are injected straight into the patient to find the right cells). In vivo methods have been used most often when it comes to viral vectors.

One of the new methods, used by Foss and colleagues, is called peptide-enabled RNP delivery for CRISPR engineering (PERC); the other, used by Zhang and colleagues, is called Peptide-Assisted Genome Editing (PAGE). They both work by accompanying CRISPR technology by a protein that can penetrate the cells to get in, as opposed to a virus. Importantly, neither of the methods use any electroporation, which uses high-voltage currents to make the cells more permeable and allows the gene editing tools to get in, but can be toxic to the cells.

Wow. How did the new methods do?

Well! So well, in fact, that in one study, successful gene-editing was observed in immune cells with 98% efficiency.

What's the takeaway?

These methods solve two of the main issues that research on CRISPR has struggled to overcome: safety and accuracy. The methods are both safer for the cells and cheaper to use.

In contrast to in vivo gene-editing approaches, ex vivo gene editing is limited to the intended target cell types. In that way, the gene-editing doesn’t have the danger of affecting cells it didn’t mean to. With a safer and more accurate way to enter the cell, CRISPR may be closer than it ever has before to being used as a therapy to treat genetic conditions.

Credit for this one also goes to a fellow Substack writer for this post. Visit Codon here: